Mid-to-late May is considered to be near the peak of the tornado chasing season across the Plains of the United States. This is a time during which most storm “chasecationers” will venture out to the Plains in hopes for at least a few days of hunting for big storms. In the past, some of the most well-known tornado chases have taken place during the second half of May across the Plains.

[When is the best time to schedule a storm chasing vacation?]

While some noteworthy tornado chases have happened earlier in the spring, as well as later in the year — such as June — climatology overlapping with great terrain seems to zero in on mid-to-late May for the peak. Earlier season events often focus in on places like Dixie that are not the most conducive for tornado chasing. Later events happen, but are often more spread out and nuanced, especially as one moves later into spring and summer. These later events also stray into parts of the Upper Midwest and Great Lakes, which are not classic tornado chase areas by most standards.

Methodology

I decided to take a look at the number of tornadoes that have been reported in the Plains between May 16-31 over the past 25 years, from 1993 to 2017. Note that data for 2018 is not complete as of this posting, so that year was not used. When considering the Plains states (Colorado, Kansas, North Dakota, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas and Wyoming), the region averaged 87 tornadoes, according to data from tornadohistoryproject.com, during the May 16-31 time period. The most was 204 in 2004, while the least was just nine in both 2006 and 2009.

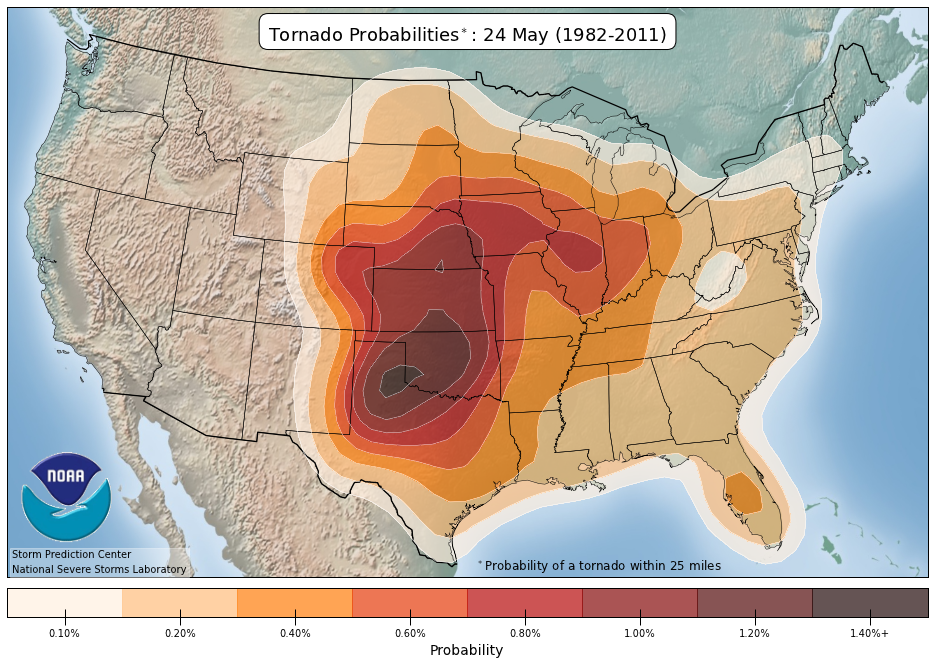

[Where tornadoes typically form in May across the United States]

Since weather patterns shift and change, I wanted to isolate stretches that saw the most and least tornado activity in that period. I considered five to 15 day blocks, as that would help to smooth out any data that was skewed by one or two substantial tornado outbreaks. In the years sampled, the most active stretch was May 22-29, 2008, when an average of 23 tornadoes occurred each day for eight days across the Plains. Note that the climatological average using 1993-2017 is about five tornadoes per day, so this was more than 300% above average. The least active stretch was May 16-28, 2006, when only three tornadoes occurred during the period. The average rounded down to zero per day for that case.

Probability of a tornado within 25 miles of a point, centered on May 24th. (NOAA / SPC)

Here are the top five stretches:

- May 22-29, 2008 – 23 tornadoes/day

- May 18-25, 2010 – 17 tornadoes/day

- May 23-28, 2015 – 16 tornadoes/day

- May 16-30, 2004 – 14 tornadoes/day

- May 21-30, 2016 – 12 tornadoes/day

And the bottom five:

- May 16-28, 2006 – <1 tornado/day

- May 16-31, 2009 – 1 tornado/day

- May 17-31, 2003 – 1 tornado/day

- May 16-27, 2005 – 1 tornado/day

- May 16-25, 2014 – 2 tornadoes/day

What weather patterns are associated with long stretches of well above average and well below average tornado activity across the Plains?

As many might expect, when there is troughing (areas of low pressure) across the western United States and ridging (high pressure) over the Southeast, tornado activity is favored over the Plains. In this scenario, the jet stream takes on a classic Four-corners region to central Plains trajectory, which is often what storm chasers look for when heading out to the Plains to chase tornadoes. With ridging downstream of the active pattern, over the Southeast, warm, moist air is often co-located on the Plains as forcing approaches from the west. This setup is conducive for severe thunderstorms, including tornadoes, over the central U.S.

Another aspect of the large scale pattern that favors an extended stretch of tornado activity is the presence of low pressure “blocking” across eastern Canada. Think of this as a roadblock that works to keep the continental U.S. pattern in place. With troughiness across the West, ridging over the East and downstream blocking across eastern Canada, the ridge, more or less, stays put. This allows for trough after trough to impinge on the Plains before the pattern eventually breaks down. The breakdown is often associated with the ridge migrating west and north, or the troughing moving toward the Midwest/Great Lakes.

Mean 500mb heights (black lines) and anomalies (shaded) for May 22-29, 2008. (NOAA / ESRL)

In extreme cases, like late May 2008, the pattern across North America was very amplified. Not only was troughing stagnant across the western U.S., but the trough was unusually deep and strong. This mean pattern was able to remain in place for over a week as an anomalously deep trough was also evident downstream, across southeastern Canada and even into New England. With a ridge in between the two features, the Plains saw day after day of tornado events, resulting in one of the most memorable chase periods in modern times.

[Weather patterns that favor lots of tornadoes during each month of the year]

Likewise, when ridging is prevalent across the central/western states, tornado activity is typically lessened. In this case, the jet stream is usually displaced to the north, west and/or east, keeping more favorable large scale forcing and deep layer wind shear away from the Plains region. Other aspects of the average unfavorable tornado pattern for the Plains include troughing being displaced west into the Pacific Ocean, troughing over the eastern U.S. and instead of low pressure blocking in eastern Canada, an anomalous ridge of high pressure is usually evident there.

Mean 500mb heights (black lines) and anomalies (shaded) for May 16-25, 2014, May 16-31, 2009, May 16-28, 2006, May 16-27, 2005 and May 17-31, 2003. (NOAA / ESRL)

Another way to look at mid to late May is to consider what the climatological average pattern looks like. The mean 500mb pattern from 1993-2017 appears to feature a ridge across the central U.S. Notice that the ridge axis is just east of the High Plains and there is some troughing along the West Coast. With minimal blocking downstream, the mid to late May upper level pattern is usually fast-paced, meaning that troughs move from west to east relatively quickly, breaking down the ridge, but then the pattern reloads over the course of a few days to perhaps a week.

[Rethinking how we conceptualize tornado days]

This is where active/quiet patterns differentiate themselves from the average pattern for mid to late May. In active years, downstream blocking and/or ridging keep the pattern going, where troughs repeatedly impinge on the High Plains. On the flip side, when ridging migrates west and north, the pattern over the Plains becomes quieter. Many storm chasers will refer to this as the “death ridge” pattern.

To summarize, tornado activity is favored in the Plains when the weather pattern features troughs of low pressure across the western half of the U.S., with ridging dominating over the eastern part of the country. The opposite is true when there is an anomalous ridge across the Plains and troughing is displaced to the Pacific Ocean and/or eastern U.S. While both active and quiet patterns usually break down and recycle over the course of a few days to a week, sometimes the pattern is stagnant, favoring an extended period of above or below average tornado activity.

There are other considerations than the large scale pattern when it comes to tornado occurrence in the Plains, but it is larger, synoptic patterns, particularly over the course of a 1-2 week period, that favor extended stretches of active tornado production.

Latest posts by Quincy Vagell (see all)

- How peak tornado season ends up active or quiet in the Plains - May 14, 2019

- Low tornado count set to continue through the end of April, but it’s too early to call the season - April 21, 2018

- June 2016 tornado outlook - May 23, 2016